When I went to the Columbia Gorge last month to explore old highway segments, the Shellrock Mountain segment wasn’t the only one I checked out — I ended up seeing 4 old sections total. The second section I’m highlighting is also the furthest east I visited: the Ruthton Point Viaduct section, a ¼-mile orphaned segment that includes about 300 feet of viaduct and stone railing. Though a small piece of the viaduct can be seen from I-84 and in a Google Street View photosphere from 2014, they don’t do it justice; the mountainside shields drivers and web-surfers alike from the beauty on the other side.

Like the last post, I’m going to dive into the history of this segment, but also add a dash of background info on Ruthton Point itself. Also like last time, you can skip ahead to the photos.

The History Lesson

So What Is “Ruthton Point” Anyway?

To answer that, we need to take a look at the life of Joseph W. Morton, a wealthy Hood River orchard owner who also listed “lawyer”, “state representative” and “one time gubernatorial candidate” among his many accomplishments. Born in Henry County, Iowa in 1865, Morton moved with his family to Oregon in 1875, eventually settling in Hood River in 1883.1 Three years later, Morton purchased 400 acres of land “three miles out from Hood River on the State road”; though he named the farm itself “Riverside Farm”, he dubbed the area “Ruthton” after his daughter Ruth Morton.2 The portmanteau was also used to name the land’s various geological features: Ruthton Hill, Ruthton Cove, and (of course) Ruthton Point.3 There was even a “Ruthton” stop along the Union Pacific Railroad line that passed through his land at one point.4

To this day, Riverside Farms is still owned by descendants of Joseph Morton.5 Primarily an apple orchard, they branched out into the cider-making business in 2013 as “Rivercider”.6

Swerving Back Onto the Highway

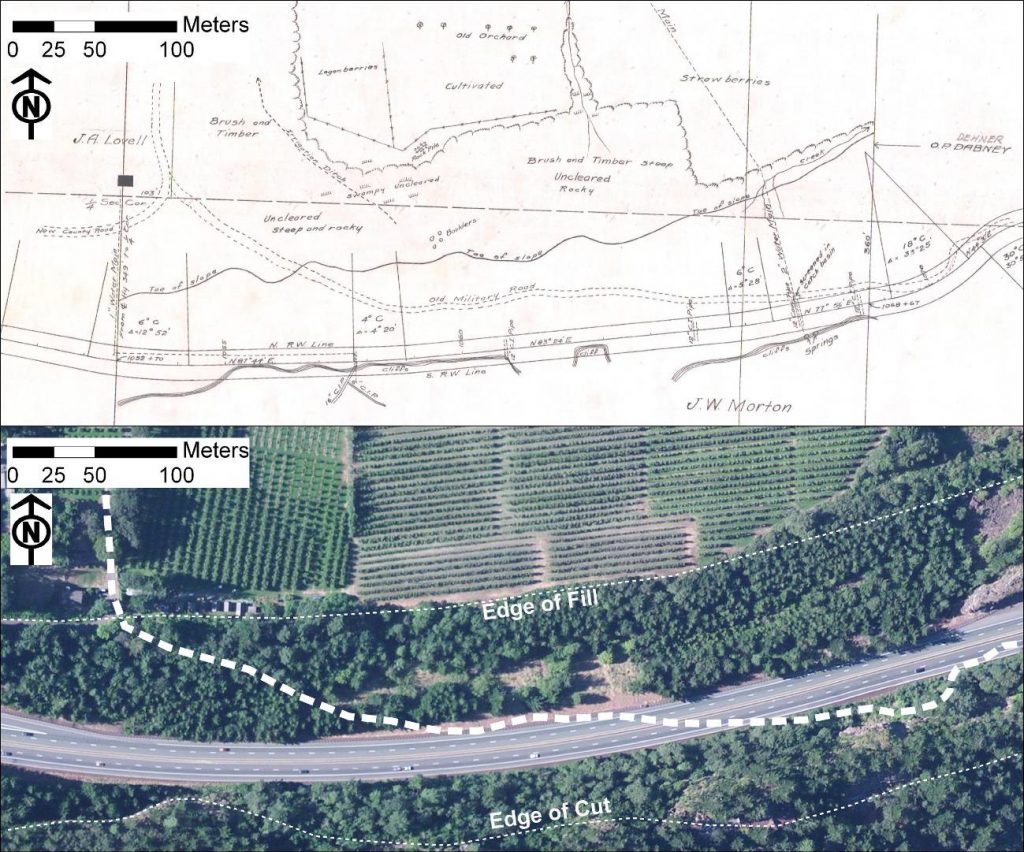

Much like the Shellrock Mountain segment, the highway history of Ruthton Point begins with the construction of The Dalles-Sandy Wagon Road in 1872-73, shortly before the Mortons arrived in Oregon — in fact, the “state road” he lived on in 1886 was this old road. While much of the wagon road within the Columbia River Gorge was obliterated when the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company built their rail line in 1882-83, the portion east of Shellrock Mountain (including through Ruthton) survived into the 20th century. A 1911 field report from S.S. Baldwin noted that the road was still being used by teamsters, but “it should be straightened and the grades improved, as they are steep in some places.”7 Unfortunately, any traces of the road in this area have either been completely destroyed by the past century of development or are on private lands unlikely to be evaluated in the field.8

When the Columbia River Highway was originally surveyed, a different alignment around Ruthton Hill was determined:

From Mitchell’s Point, the location follows the existing road for one-half a mile, then swings south, eliminating two railroad crossings, and climbs on a three per cent grade to a junction with the present road at the top of Ruthton Hill.9

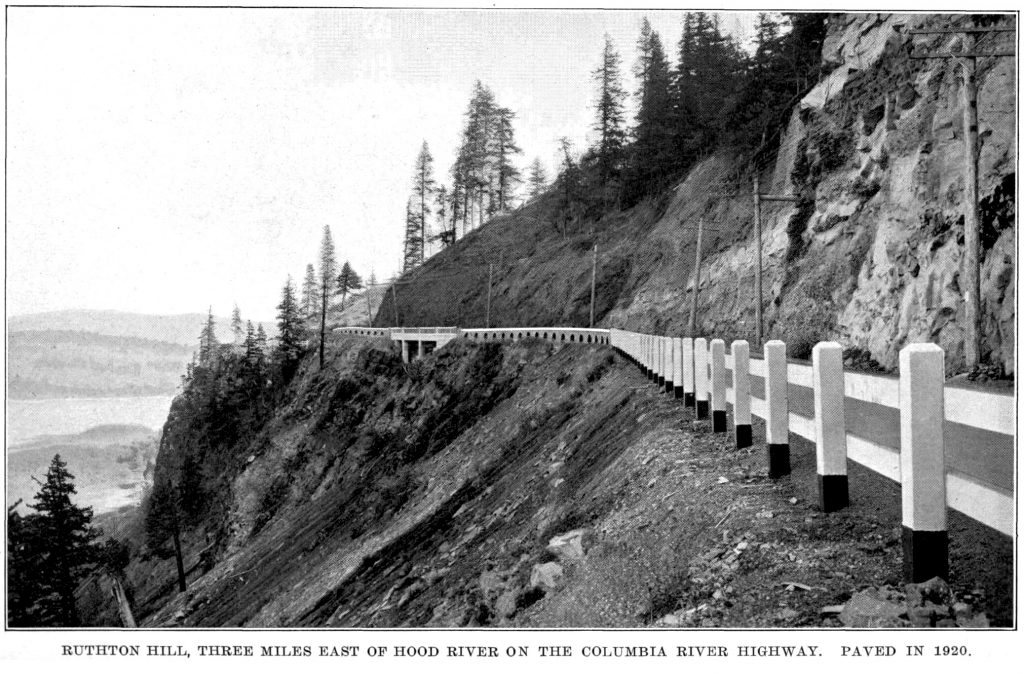

Grading and construction work on this part was completed during the 1917-1918 biennium at a cost of $107,369.69; this included $1,362.51 for the 50-foot reinforced concrete “Ruthton Viaduct” at Ruthton Hill.10 In today’s dollars11, that translates to just over $1.7 million, with the viaduct work costing a little under $22,000.

After it opened in 1918, the Ruthton Viaduct section was known for its spectacular vistas of the Columbia River, Mitchell Point and Washington’s Underwood Mountain. However, its abandonment follows largely the same trajectory as the Shellrock Mountain segment, left to rot just outside of view of the new freeway completed by 1954.12 To keep their access, the residents of Ruthton Point were provided with their very own “hidden” exit on I-84 westbound — it doesn’t have any signage indicating what the exit is for, not even an exit number. (Diane Ochi wrote that this portion was accessed “using the exit marked ‘Service Road’”, which is incorrect.13 The Service Road exit is a half mile further west, which also connects to a segment of the old HCRH.)

When this segment was revisited in the 1980s, it was in a pretty sad state. It had been used as a dumping ground, “piled with boulders and aggregate from freeway construction”14 and used as a “stockpile area for highway sanding projects”.15 Both the viaduct railing and the pavement were deteriorating, and the road was covered in gravel. Some of the stone guardrail had been damaged by the boulders when they were initially dumped on the site. Finally, it was gated off on the eastern end to prevent trespassers from accessing it.

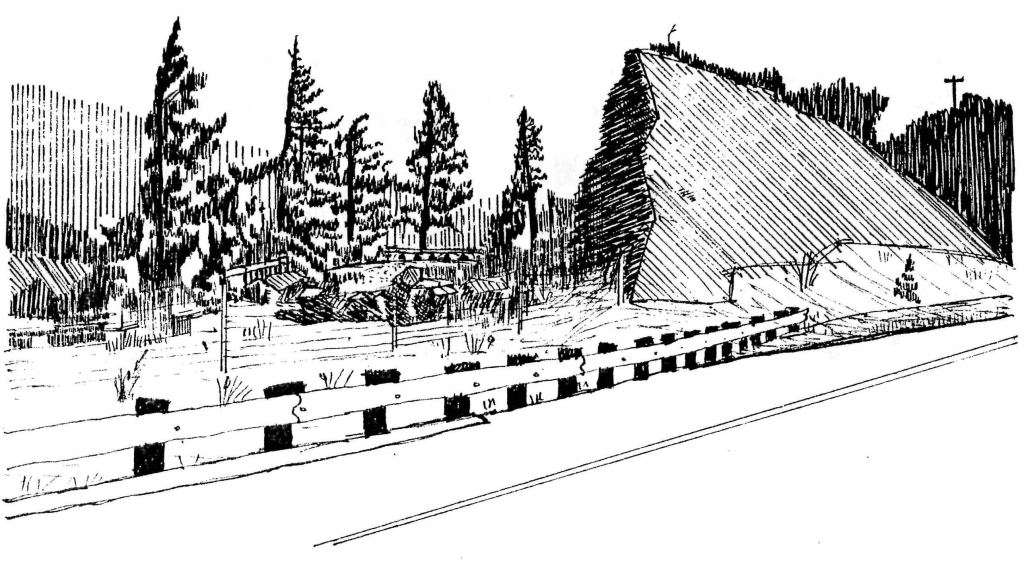

Ochi’s original 1981 recommendation for this segment acknowledged that it offered some pretty stunning views of the Gorge, an ideal location for a scenic highway rest stop. To accomplish this, she proposed a seven-part program for a minimal level of site development:

- Clear the roadbed of rock and aggregate.

- Grade the cut slopes into less severe, more natural-looking hill forms.

- Plant the regraded slopes to better screen the center of the fragment from the freeway.

- Provide a small number of temporary parking spaces near the east end of the fragment.

- Provide a path over the old highway surface from the parking area to the viaduct and guardrail area.

- Provide an interpretive sign near the viaduct and guardrail area giving historic information on the highway.

- Restore or at least stabilize the viaduct and stone guardrail.16

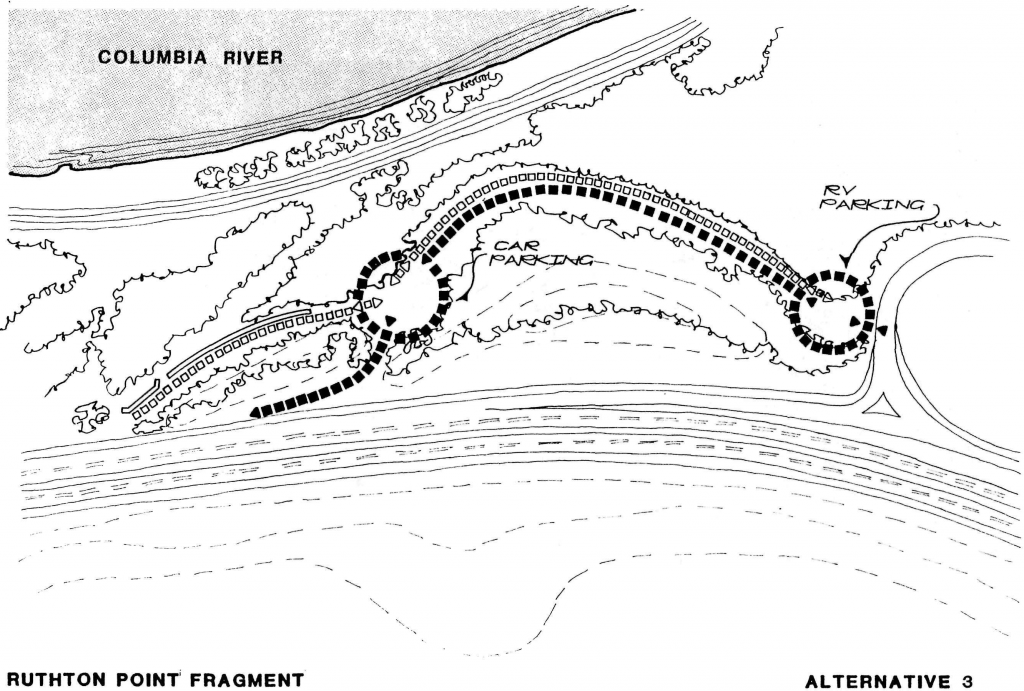

Ochi further emphasized that any work done should allow for expansion if public use increased, and included three maps of possible improvement plans to illustrate that point. Alternative 3, her most ambitious, would have allowed cars to drive one-way down roughly 60% of the segment to a small parking lot, exiting via a new onramp to I-84 westbound. In addition, RVs would park at the eastern end — though after visiting the site myself, that might be wishful thinking without altering some of the terrain and existing roadways.17

When ODOT released their study of the highway corridor in 1987, they too thought the site could serve as a small wayside for the travelling public. They recommended placing a small parking area at the eastern end of the segment, allowing access to pedestrians only beyond that. The plan didn’t explicitly call for adding anything more than parking and interpretive signage, nor did it discuss future expansion; ODOT decided that “[m]inimal development is desired” and felt that it “will never be a major tourist stop.” Still, the viaduct and rock railings were crumbling and the pavement was deteriorating, so they considered it a medium priority project. The budget for all these improvements was $25,000, but they were unfunded at the time of the study.18

Possibly as a result of the 1987 study, that same year the Oregon Legislature directed ODOT to spearhead efforts to preserve and restore remaining sections of the HCRH, including a plan to reconnect these sections as a State Trail.19 As a result, ODOT did manage to find some money to clear the roadbed and repair the viaduct and stonework at Ruthton Point. The work was performed during the summer of 1992 under the supervision of Oregon State Stonemason Richard Fix.20 Included in the restoration was the inclusion of an “observatory” balcony similar to the one at the Rowena Loops; its foundations were rediscovered after clearing away the rocks and debris that covered the road.21

In 1996, ODOT released the Historic Columbia River Highway Master Plan, a guide for the future restoration of the old highway and construction of connecting segments of the remaining abandonned sections.22 The Ruthton Point section acknowledged the restored rockwork and advocated connecting it to “a bicycle facility along the northern slope of I-84” from Hood River to the frontage road near Mitchell Point.23 In addition, the plan recommended a small parking area to connect to the trail, as well as a possible picnic area somewhere sheltered by the wind.24

Despite being tied for the second-highest priority HCRH restoration project, funding for this section was again a concern. The price tag for this connection came to $2.806 million, or about $4.662 million in today’s dollars.25 However, other issues remained before this segment could be connected to the rest of the system:

- Placing the parking area at the eastern end of the segment would drastically negatively impact the intersection with Morton Road, so ODOT recommended moving it towards the western end.26

- In addition, ODOT “should strive to bring the currently substandard [Morton Road] exit up to state standards lo the maximum extent feasible before project implementation”, which would drive up costs more.27

- Finally, there was (and likely remains) some dispute about who owns the land along that section; ODOT research indicates that they own it, but the adjacent property owners (likely the Struck family, who are the descendants of Joseph Morton) also claim ownership.28

All of these matters are likely why, aside from the 1992 stonework rehabilitation, no other efforts have yet broken ground to improve this section, despite plans as late as 2011 showing a possible completion by 2016.29

ODOT still does plan to connect this segment to the larger trail. The most recent construction information I’ve seen has come from a November 2016 FLAP funding request flier, showing a construction date of 2022 at a cost of $10 million for a mile-long section from Ruthton Point to nearby Ruthton Park.30 That 2022 date might be a bit optimistic, but the wheels are still apparently moving towards an eventual reconnection.

The Pretty Pictures Part

All photographs after this point were taken by me in November 2019 unless otherwise noted.

Additional Notes

By contrast to the Shellrock Mountain segment, this one was much easier to access. You simply pull off I-84 westbound at the unmarked exit past Exit 62, continue past Morton Road, and pull off onto the right shoulder on the onramp. From there, it’s just a short walk to the spot where you can take a look at the segment. It’s ODOT property from I-84 up to the power lines — which I didn’t realize until after I traversed this segment in full — so be careful about where you wander. At least you can enjoy some spectacular views of the Columbia River Gorge on a viaduct or observatory state tax dollars helped restore some 30 years ago.

Next up: Returning to the Wyeth area for a couple of short nondescript segments. Won’t be as much history in that post, but due to photo editing will still probably only come in the new year. See you next decade!

Edit 1/7/2020: I added a photo of Ruthton Hill from the 4th Biennial (1919-1920) Report of the Oregon State Highway Commission. Hat tip to the Recreating the Historic Columbia River Highway Facebook group for the discovery. The associated website is slowly coming back online, which is exciting — I loved checking it out when it was still up, and I look forward to seeing it again.

Footnotes

- “Morton, Joseph W.”. Oregon Historical Society Digital Collections, https://digitalcollections.ohs.org/morton-j-w-2, accessed 3 Dec 2019.

- An Illustrated History of Central Oregon: Embracing Wasco, Sherman, Gilliam, Wheeler, Crook, Lake and Klamath Counties. Western Historical Publishing Company, 1905, p. 353

- Ochi, Diane. Columbia River Highway Options for Conservation and Reuse, 1981, p. 116. (mirror)

- McArthur, Lewis A. & Lewis L. McArthur. Oregon Geographic Names. Oregon Historical Society Press, 2003.

- “Rivercider: History of the Farm”. Riverside Farms, http://www.rivercider.com/riverside, accessed 8 Dec 2019.

- “Rivercider”. Riverside Farms, http://www.rivercider.com, accessed 8 Dec 2019.

- “‘Twixt-Falls Way Will be Graded.” The Sunday Oregonian, vol. XXX, no. 27, 2 July 1911, p. 5.

- Connolly, Thomas J. et al. The Dalles to Sandy River Wagon Road Through the Columbia River Gorge, Oregon: An Inventory and Evaluation. University of Oregon Museum of Natural & Cultural History, Oct 2013, p. 22. (mirror)

- Bowlby, Henry L. First Biennial Report of the State Highway Engineer. Dec 1914, pp. 152-153.

- Oregon State Highway Commission. Fourth Biennial Report. Dec 1920, p. 252.

- October 2019 dollars

- Oregon State Department of Transportation. Historic Columbia River Highway Cultural Landscape Inventory: Shellrock Mountain to Ruthton Point, Jan 2010, p. 18. (mirror)

- Ochi, p. 116

- ibid.

- Oregon Department of Transportation. A Study of the Historic Columbia River Highway, Nov 1987, p. 103. (mirror)

- Ochi, p. 118

- ibid., pp. 118-122.

- ODOT 1987, p. 72.

- Hadlow, Robert W. et al. Historic Columbia River Highway Oral History. Oregon Department of Transportation, Aug 2009, p. 7. (mirror)

- “Transformation at Ruthton Point.” Friends of the Columbia Gorge Newsletter, Friends of the Columbia Gorge, Fall 1992, pp. 1 & 3. (mirror)

- ibid.

- Oregon Department of Transportation. Historic Columbia River Highway Master Plan, Feb 1996, p. 1. (mirror)

- ibid., p. 21

- ibid., p. III-23

- ibid., p. 53

- ibid., p. III-23

- ibid.

- Oregon Department of Transportation. Historic Columbia River Highway Master Plan, Revised Jan 2006, p. 105. (mirror)

- Oregon Department of Transportation. Historic Columbia River Highway State Trail Plan, Wyeth to Hood River, 13 Jan 2011, p. 42. (mirror)

- Oregon Department of Transportation. Historic Columbia River Highway State Trail — F.L.A.P. Program Request “The Final Five Miles”, Nov 2016.

Jonathan, another great report on what is likely the most interesting HCRH fragment remaining. I’ve seen it speeding by on the freeway countless times, so it was awesome to see it in detail.

I think there is a decent drive in ODOT and OPRD to finish the state trail, it’s just a matter of money being made available. I believe Mitchell Point is the next priority and I think I read that at least the engineering study is funded. I doubt if they’ve set aside money for the actual construction, since I don’t think they’ve definitely decided between tunnel or viaduct or some combination. The last I heard, the remaining sections east and west of Mitchell Point still have no identified funding in the coming biennium, so I agree with your skepticism with their claim that the State Trail will extend around Ruthton Point by 2022. Maybe you have some more information here?

Thanks @Chris. You should pull over and take a look one of these times yourself.

I do want to clarify that while I believe that the HCRH State Trail will be completed through Ruthton Point, my comment was solely about construction being completed by 2022. Like you said, I think we’re pretty much stuck until a design for Mitchell Point comes out. The November 2016 FLAP request I mentioned pegged that section as the #1 priority requiring $22.5 million for completion, $4.5 million for the design (marked “10% complete”) + alternatives study (completed) and $18 million for the actual construction. The total FLAP request was for $27.82 million with $3.18 million in matched funds, but I have no idea if they actually received it. Both lists for Oregon’s 2016 and 2018 FLAP proposals show HCRH reconnection projects, identified as OR-FY16-08 and OR-FY18-45 respectively, but doesn’t show the amounts to be considered. Further, OR-FY16-08 doesn’t name a specific segment of the HCRH, but OR-FY18-45 is for Viento-Mitchell Creek… which is different than Mitchell Point. I think I might need to contact the ODOT Region 1 people to see if they have any updated info or scheduling.